2018

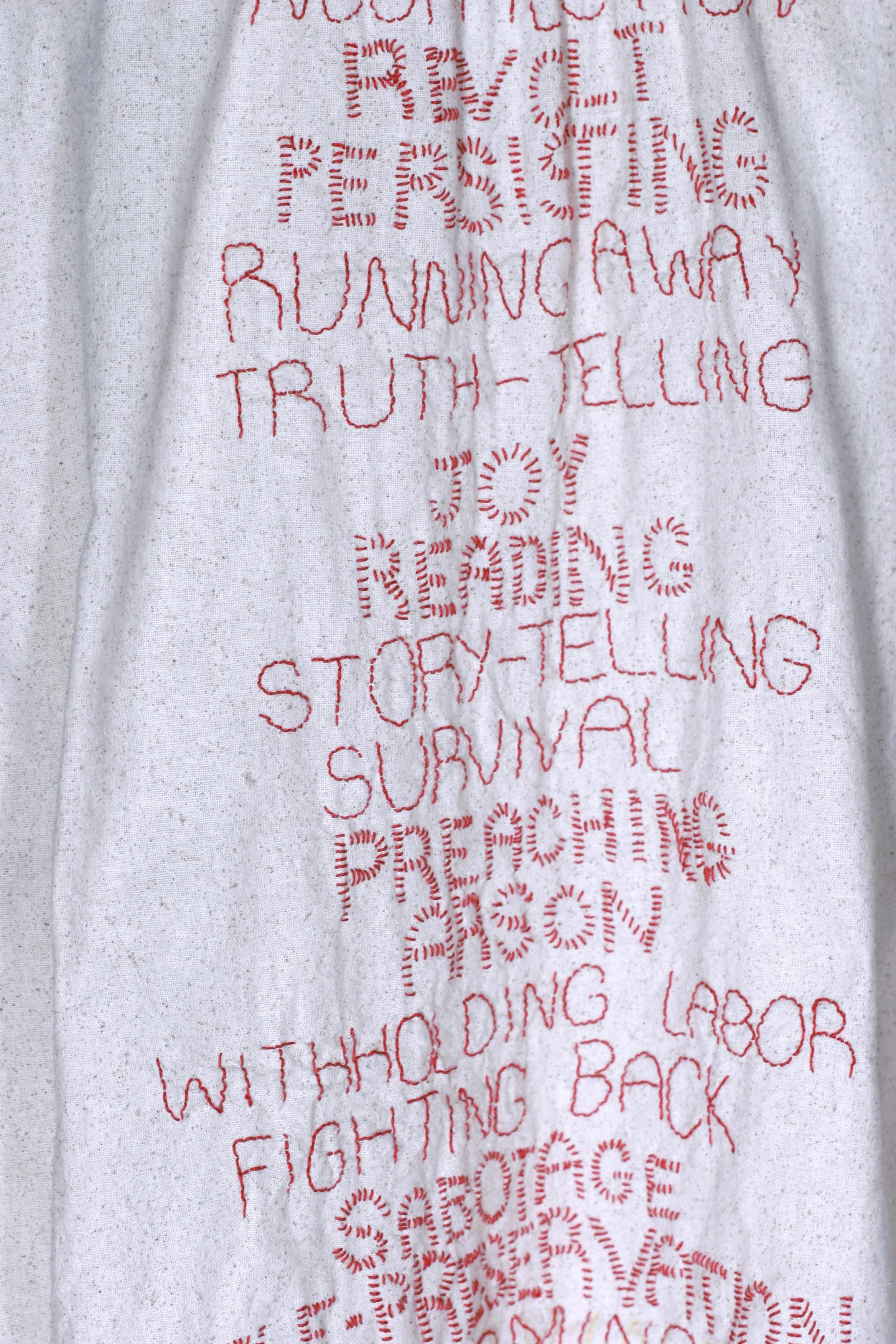

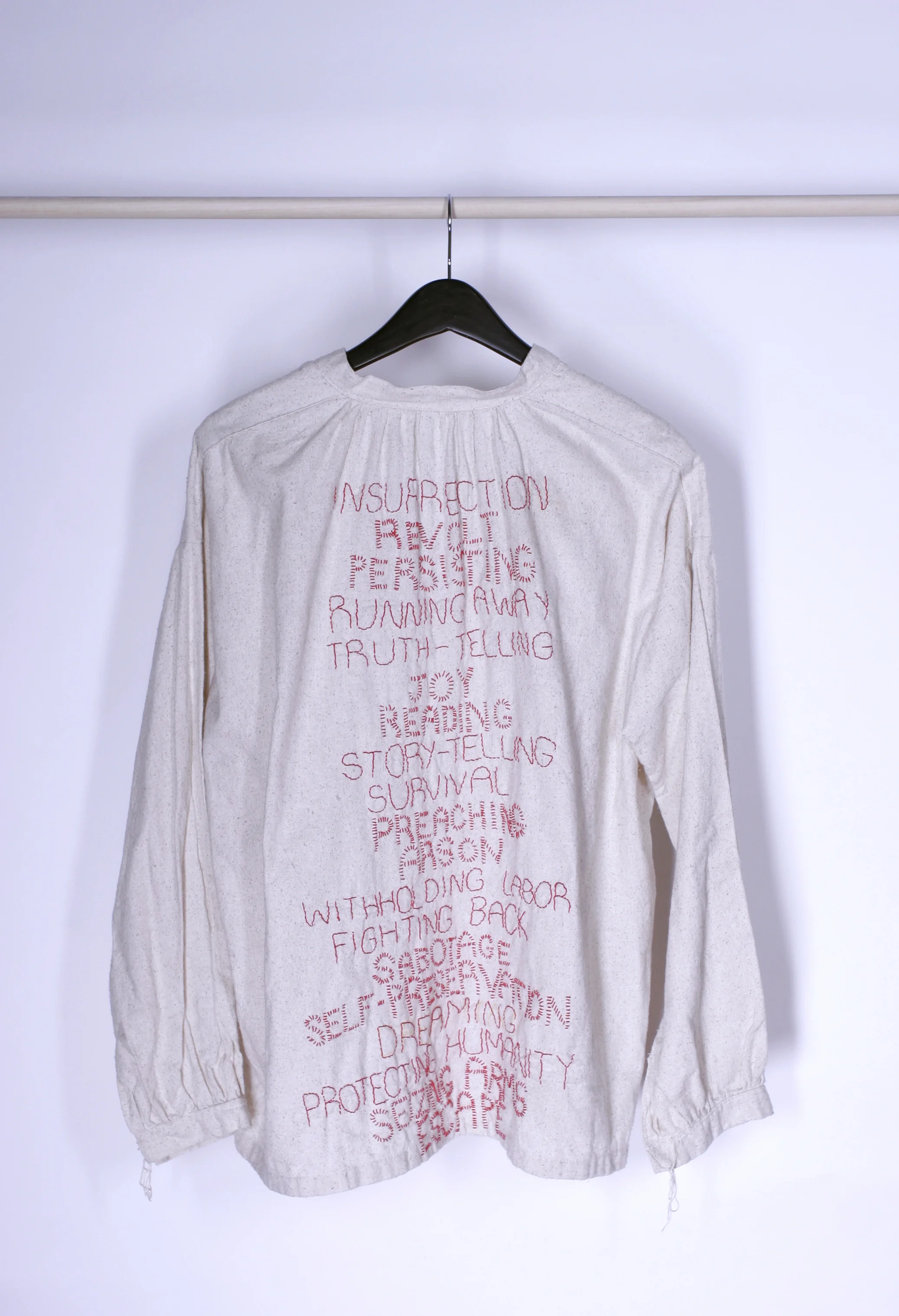

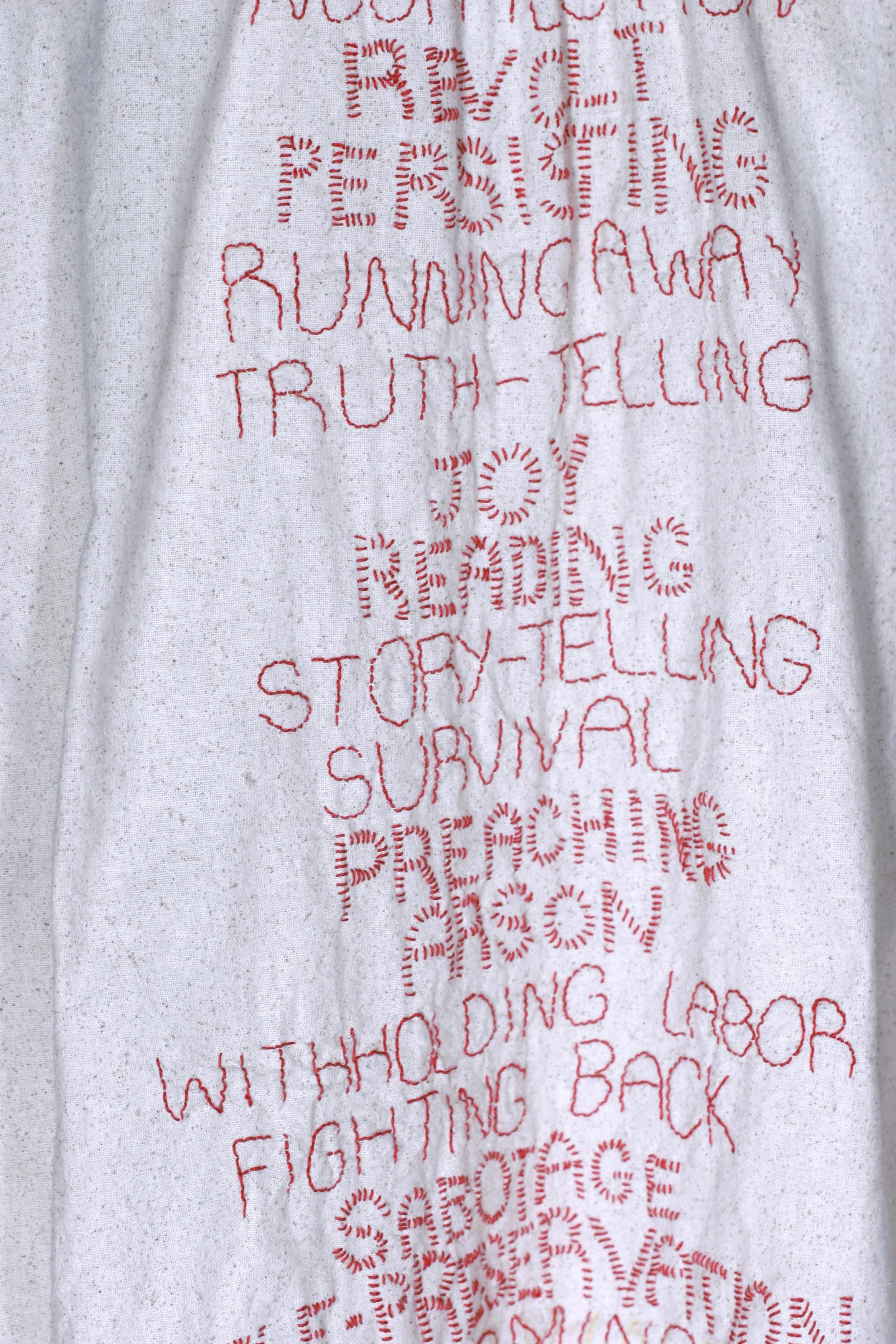

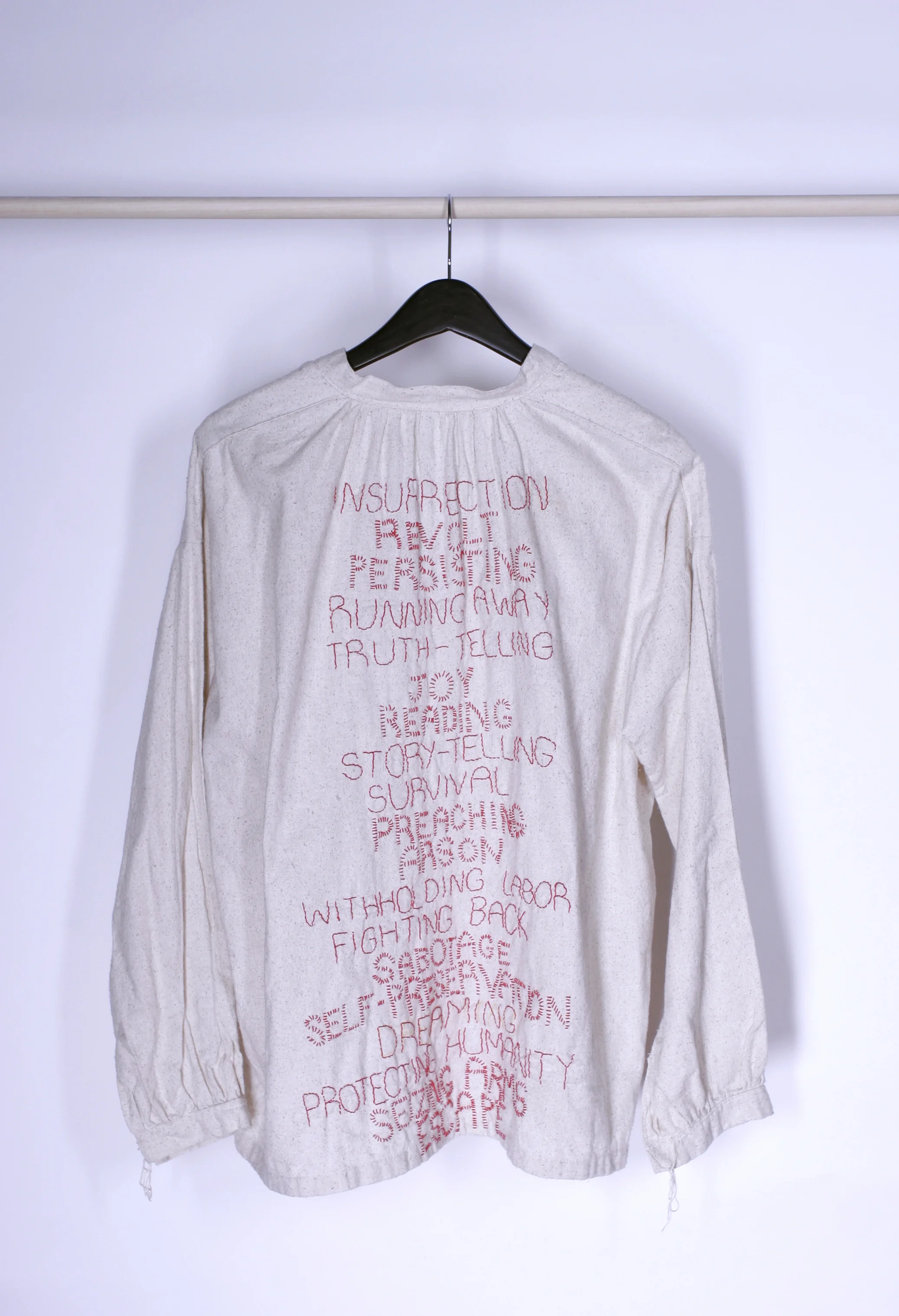

This piece was commissioned by, and donated to, the Benjamin Banneker Museum. It honors Benjamin’s father, Robert Bannaky, and his resistance to and escape from slavery. In this intimate monument, embroidered words honor the variety of ways that resistance manifests, offering a chance for you as a viewer and me as an artist to reflect on the less obvious forms that it can take. Since Robert Bannaky did not write his own story, to choose these words, I relied on the writing and oral history of two other people who were enslaved in the US: Fredrick Douglass, and Oluale Kossola, also known as Cudjo Lewis.

Fredrick Douglass wrote about how imagining himself as a free man, and seeing enslavement as a temporary injustice that must be changed, was to resist bondage. “From my earliest recollection, I date the deep conviction that slavery would not always be able to hold me within its foul embrace.” He describes how this conviction created hope, the possibility of joy, and provided an explanation for the deep sorrow he often felt. He writes about how the gospel songs of enslaved people were an expression of these complex feelings: “Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.”

Oluale Kossola’s oral history led me to the words “truth-telling” and “story-telling.” Kossula was the last living survivor of the trans-Atlantic slave trade from West Africa to the US. When Zora Neale Hurston interviewed him in 1927, he recalled detailed memories of the torture, violence and abuse he endured while enslaved. His ability to share this testimony decades later meant that he could tell the world about the injustice done to him. It also meant that he remembered his ancestors, his culture, and what it was like to be free, and that he passed this memory on to those around him, and now to those who can read his story.